By Adi Khen

As a first-time volunteer at the Smith lab, I got to be involved in one of the most exciting parts of data processing: drying, weighing, acidifying and, basically, slaughtering CAUs!

Let me explain… CAU stands for Calcification Accretion Unit, or in this case a set of two stacked PVC tiles that are used to measure carbonate accretion and successional development on coral reefs. Three years ago, PhD student Levi Lewis installed 160 CAUs across 8 different reef sites on leeward Maui. Half of the CAUs at each site were “caged,” or enclosed in a stainless steel frame to prevent herbivory, while the rest were “uncaged.” Environmental characteristics at each site, such as temperature, light, pH, salinity, and sedimentation were also measured. By installing and later removing CAUs, researchers are able to sample reef communities without causing extensive damage to the reef.

This past summer, Levi removed all of his CAUs from the reef and brought them back to the lab. The macroalgae that had grown on the tiles, as well as the sediments that had collected on the tiles and the cryptic invertebrates that found shelter among them, were put into separate bags and frozen for future processing. All tiles were photographed for image analysis and then, our slaughterhouse was open for business.

We dried the tiles in a drying oven, weighed them, let them soak in acid until all of their calcified matter dissolved, scraped them, and then dried and weighed them again (the difference between the initial and final tile masses would then represent the amount of carbonate accretion). We also filtered out the remaining fleshy matter from each tile, dried it, and weighed it to find the amount of fleshy biomass on each tile. After several months of the lab reeking of acid, we were left with about 300 clean PVC tiles, and we moved onto our next subjects: the macroalgae and invertebrates.

Macroalgae samples were also collected from the tiles in Maui, and were frozen for later analysis. Well, we thawed them, sorted each CAU’s algae by type or species, dried them, and then weighed them individually. We could then compare not only the difference in macroalgal cover between sites, but also the density and diversity of the macroalgal communities.

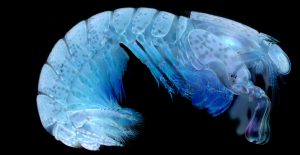

As for the frozen invertebrates, we thawed them, too, sieved them into different size categories, and then identified and quantified the critters from each CAU. This would help us determine the diversity, abundance, and potential importance of cryptic invertebrates in benthic communities.

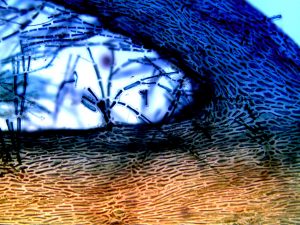

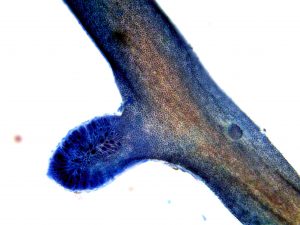

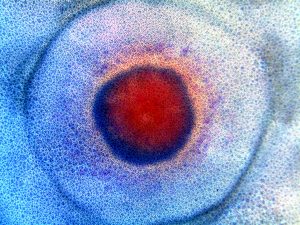

Microscope view of a stomatopod found on one of the CAUs

Inverted microscope view of the same invertebrate (which I like to call, “inverted invert”)

These days, though our slaughterhouse is no longer in session, we’re getting ready to photoanalyze the surfaces of each of the CAUs to get a better picture of benthic community development on Maui’s reefs.