By Niko Kaplanis

In April of 2006, during a survey for the Channel Islands Research Program (CIRP), renowned scientists Kathy Ann Miller and John Engle discovered an established population of the invasive alga Sargassum horneri near the Wrigley Marine Science Center at Santa Catalina Island. This was the first instance of the species being documented at one of California’s offshore islands. Reconnaissance surveys spurred by this initial discovery then revealed established populations at San Clemente Island in May of 2007, and subsequently, populations have been discovered throughout the rest of the Channel Island chain. S. horneri has now become very well established at Catalina, expanding its range to occupy the entire leeward (north) side of the island, as well as some locations on the more exposed and native-algal dominated south shore, and flourishing through multiple generations.

In the past month I visited Catalina to assist with ongoing research on the S. horneri invasion at Catalina lead by Lindsay Marks, a PhD student at UC Santa Barbara. Lindsay has undertaken a heroic effort — conducting monthly surveys at sites throughout the leeward side of the island and running multiple removal experiments—with the goal of tracking the invasion and providing detailed information on the ecology, life history, reproductive capacity, and impacts of this species.

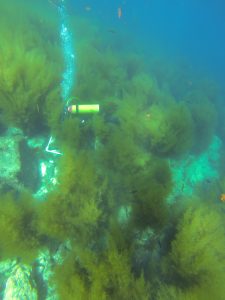

The visit provided mind-blowing insight into how dominant S. horneri can become at invasion locations. Each of the nine sites we dove was entirely dominated by thickets of the invasive alga growing in incredible densities extending from the shallow sub-tidal down to depths of 60 or 80 ft. Both the densities and abundances observed at Catalina far exceed those of San Diego, which may be a result of the longer invasion history at the island, a difference in the invasion environment, or some other as-of-yet unknown factor. The island is also starkly devoid of native Macrocystis pyrifera, the giant kelp that typically forms kelp forests along the island’s coast. While this phenomenon can’t be directly attributed to the Sargassum invasion – other factors such as persistently warm water ocean temperatures in the area are also likely in play—it is reasonable to assume that the invasion is contributing to it.

The island provides an exciting opportunity to study the invasion, and I am grateful to Lindsay Marks for inviting me to assist with her research. Whether the population will remain persistent in the current densities and spatial abundances, and whether an invasion on the scale observed at Catalina will occur elsewhere is unclear, but her work is sure to provide some insight into these questions.