By Samantha Clements

Algae, often referred to as “seaweed,” are underwater “plants” that, unlike land plants, lack a vascular system. Algae live underwater and obtain water, nutrients, and sunlight directly from the environment. Because algae don’t need a vascular system, they come in many shapes and sizes and may look very different from land plants. Some algae, such as Ventricaria (“Sailor’s Eyeball”), can exist as a single cell that can grow to be larger than 10 cm in diameter!

For many people, algae on coral reefs are synonymous with environmental decline. Often the presence of algae is associated with terms such as “harmful algal bloom” and “eutrophication,” which imply the negative effects of too much algae in an environment. It’s true that under some conditions algae can grow uncontrolled and become a problem for reef-building corals, as they compete for both space and sunlight on the reef. One thing that can lead to an overgrowth of algae is an excess of nutrients in the water, either naturally from upwelling of nearby nutrient-rich waters, or from anthropogenic sources, such as agricultural runoff from land. These nutrients act as fertilizers for plants on the reef, allowing them to grow very quickly. Another thing that can cause algae to grow uncontrolled on a reef is release from the pressure of herbivory. This is often caused by overfishing in communities where reef fish and other herbivores, such as sea urchins, are consumed as an important source of dietary protein.

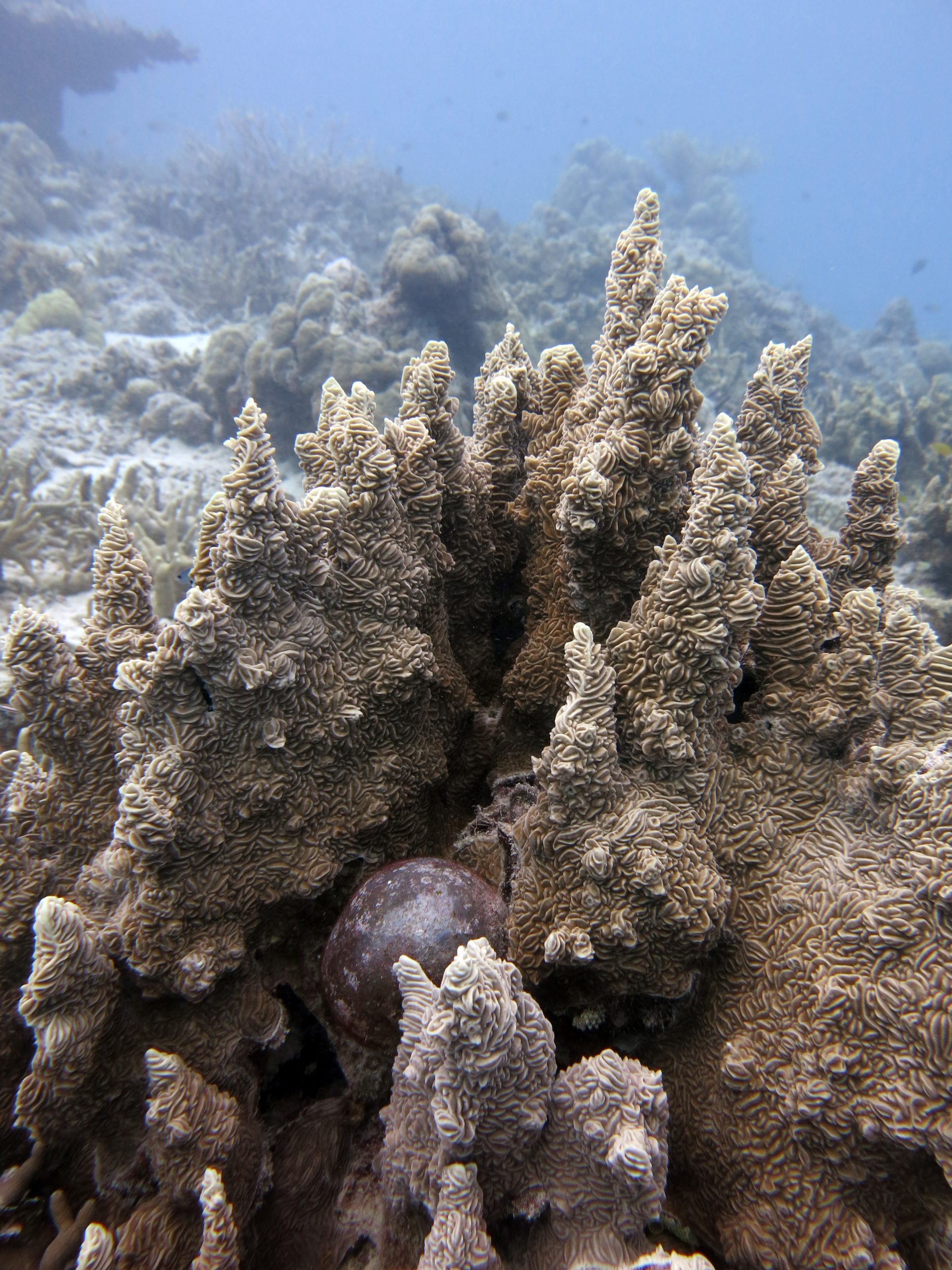

Algae, however, are very important to a healthy coral reef ecosystem under natural conditions. They provide important habitat for many small creatures and act as the base of the food chain that fuels the community of coral reef critters. Algae come in all shapes, sizes, colors, and textures and have about as many functions as faces! Halimeda, a bright green, segmented alga, has branches that contain calcium carbonate—these calcified segments become sand on the reef when they fall off and crumble. Crustose coralline algae (CCA) is a type of red, calcified algae that grows as a pink crust on the reef and is often referred to as the “cement of the reef” because it grows over loose bits of reef and essentially glues them together. It also provides a very important substrate for coral larvae to settle on. Turf is an assemblage of small, primarily filamentous, algae that grow as a dense mat. Turf is an important food source for herbivorous fishes and sea urchins, and fills most of the space on the reef where corals aren’t already growing. Many algae add to the natural beauty of the reef, such as the bright red blades of Peyssonnelia growing in shady overhangs, and the curly-cues of Padina growing between corals wherever there’s space.

This Phyllidia nudibranch makes its way through a dense bed of Halimeda

In the Smith Lab, we often collect algae to make algal pressings for our herbarium, a collection of pressed and dried algae with information about the date and location each specimen is found. Algal pressings can be very beautiful, often resembling intricate watercolor paintings. They provide important information about which algae grow in various environments and act as a catalog of diversity for the places we’ve been.

While algae have the potential to become a nuisance, they are always part of a healthy reef community. There are natural fluctuations in the abundance of algae found on a reef, but the most important things we can do to ensure algae don’t get out of control are to protect our reefs from overfishing and pollution. The rest is up to nature!

Herbarium pressing of Caulerpa

Herbarium pressing of Padina

Herbarium pressing of Portieria