By Abby Cannon:

This September I left my usual seagrass habitat and helped the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation survey corals on the Great Barrier Reef. Somewhere in the midst of identifying all of the corals within a ten meter by one meter belt at various sites I reached the conclusion that everybody interested in corals needs to visit the Great Barrier Reef at least once.

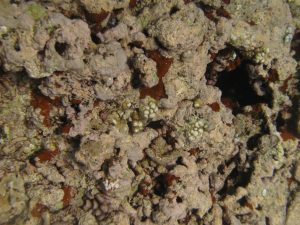

One reason the Great Barrier Reef should be on every coral aficionado’s must-see list is the amazing diversity of corals. According to J.E.N. Veron and Mary Stafford-Smith the Great Barrier Reef is home to between 300 and 500 coral species. This gives coral admirers a much better chance of seeing something new on every dive than they would get in less-diverse locations like Hawaii and the Caribbean. Even divers who do not know much about different coral species will be impressed by the amazing range of coral colors and growth forms. I can say that I probably recognize three times as many coral genera as I did before this trip.

Another reason to visit the Great Barrier Reef is to get a better idea of what a healthy reef looks like. Many reefs around the world have been so degraded for so long that the people who claim to know them underestimate the damage, because they have forgotten what a healthy reef looks like. The Great Barrier Reef serves as a reminder of how those reefs looked in the past and set higher goals for how they should look in the future with better management.

Unfortunately, not even the Great Barrier Reef is immune from degradation and some of the sites we visited reflected this. Excessive sediment and nutrient pollution can favor the growth of algae over corals and interfere with the reef’s ability to recover from events like cyclones as algae rather than coral grows back. Outbreaks of crown of thorns starfish, voracious coral predators, also seem to worsen when nutrient pollution becomes excessive. If Australia wants the Great Barrier Reef to continue being the world example of a healthy reef, these problems will need to be overcome.